In 2008, Russian collector and philanthropist Dasha Zukhova founded the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, with a mission to bring Western contemporary art, previously little known in the country, to a wider Russian public. After initially opening in the Bakhmetevsky Bus Garage, designed by avant-garde architect Konstantin Melnikov in 1926, the museum moved to a temporary pavilion by Shigeru Ban, but has now just reopened in a brand-new permanent home: the Vremena Goda (four seasons) Pavilion in Gorky Park, renovated by Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas. He spoke to Numéro about this key project.

Numéro: Can you tell us about your new Garage Museum in Moscow?

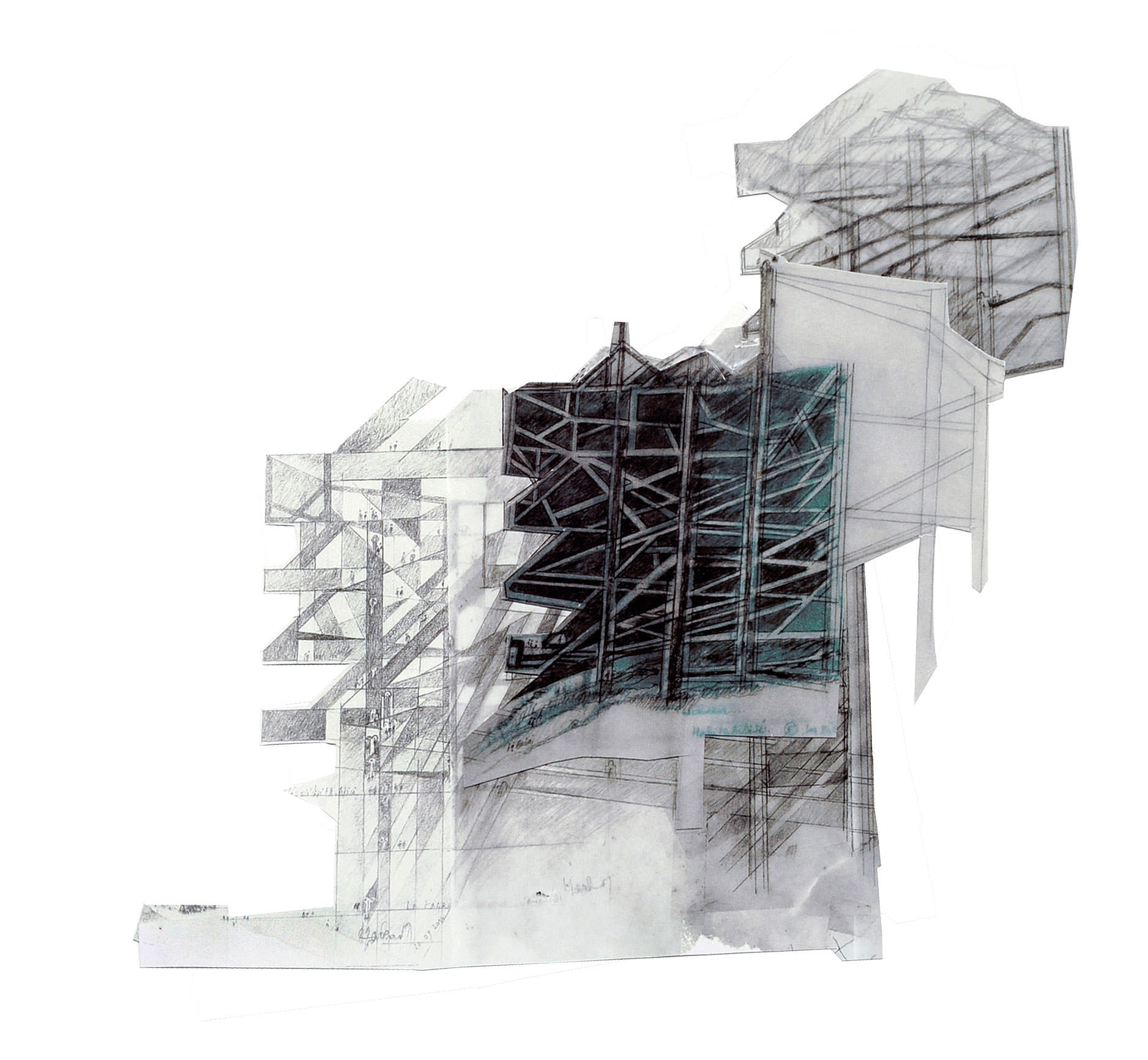

Rem Koolhaas: Dasha Zukhova’s cultural institution is very impressive, and in a crucial moment offered Moscow a very important place. It was originally in Melnikov’s Bakhmetevsky Bus Garage, but had to leave, and has now moved to Gorky Park, which is very beautiful and is also a key part of Moscow’s social life. The new pavilion was a 1960s Soviet restaurant, which had been abandoned for decades, and which we’ve converted into something new. So for me what was exciting was to focus on preservation, and I also have a longstanding interest in Russia and Russian architecture. Our thesis was that you can say many things about the Soviet period and Soviet culture, but buildings for public use were very generous and very welcoming. So we’ve tried to preserve that generosity and use it for a cultural institution. We wrapped the building in a new way, but tried to let the interior speak for itself. And we’re experimenting with a form of preservation where we also preserve to some extent the decay – the walls are kind of broken, and we’ve kept some of that.

Numéro : Comment avez-vous abordé cette rénovation architecturale ?

Rem Koolhaas : Il s’agissait ici avant tout de préserver une œuvre architecturale russe, qui est très intéressante. On peut dire et penser bien des choses au sujet de la période soviétique et de sa culture, mais le fait est que les bâtiments construits pour un usage public étaient très accueillants. Nous avons donc voulu préserver cette générosité, et la mettre à profit pour une institution culturelle. Nous avons changé son emballage, si j’ose dire, en laissant l’intérieur parler pour lui-même. La conservation de ce qui est historique est centrale dans ce genre de projet. Ici, nous expérimentons une nouvelle sorte de travail : nous avons cherché à préserver également l’état de délabrement du bâtiment. Certains murs sont très abîmés, et nous les laissons tels quels.

Yayoi Kusama is one of the first artists invited. Infinity Mirrored Room, The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, 2013.

Numéro: Contemporary art varies greatly in its dimensions, from small objects or paintings to huge installation pieces. How did you deal with this?

Rem Koolhaas: We’ve been involved with many museums, and I think that one of the few really original things about our work is that we’ve been thinking about scale almost independently of any other issue. I did a book [S,M,L,XL, 1995] which is only about scale and not about content. You have to ask why artworks are getting bigger and bigger, and of course it has a direct connection with the economy and with America. So in a certain way, I think it’s important for architecture to give a kind of resistance to this endless expansion. When we took part in a competition for the Tate, the director warned us that artists don’t appreciate the pressure of architecture, and that their preferred environment today is the former industrial space with white walls. So that made me super sceptical, and from then on I started to wonder, “Should you really indulge this or not?”

By Delphine Roche

Yayoi Kusama, Dots Obsession, 2013.

ArtCultureArchitectureArchitecture Art Garage museum contemporary art moscow OMA Rem Koolhaas Dasha Zhukova Katharina Grosse Yayoi Kusama Vremena Goda Yayoi Kusama Delphine roche Numero Magazine50

ArtCultureArchitectureArchitecture Art Garage museum contemporary art moscow OMA Rem Koolhaas Dasha Zhukova Katharina Grosse Yayoi Kusama Vremena Goda Yayoi Kusama Delphine roche Numero Magazine50

Katharina Grosse is one of the first artists invited. Inside the Speaker, 2014.

ArtArchitecture

ArtArchitecture

Architecture50Cover

Architecture50Cover

Architecture50Cover#ffffff

Architecture50Cover#ffffff

CultureExhibitionArchitecture

CultureExhibitionArchitecture

ArtPortraitArchitecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

ArtPortraitArchitecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

Architecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

Architecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

ArtArchitecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

ArtArchitecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

Architecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

Architecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

FashionArtArchitecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

FashionArtArchitecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

Architecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

Architecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

Architecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

Architecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

Architecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

Architecture50Cover#ffffffAligner à gauche

ArtArchitectureArt50Cover#f6f0f0Aligner à gauche

ArtArchitectureArt50Cover#f6f0f0Aligner à gauche Serpentine Pavilion 2017, designed by Francis Kéré. Serpentine Gallery, London (23 June – 8 October 2017) © Kéré Architecture, Photography © 2017 Iwan Baan

Serpentine Pavilion 2017, designed by Francis Kéré. Serpentine Gallery, London (23 June – 8 October 2017) © Kéré Architecture, Photography © 2017 Iwan Baan  Serpentine Pavilion 2017, designed by Francis Kéré. Serpentine Gallery, London (23 June – 8 October 2017) © Kéré Architecture, Photography © 2017 Iwan Baan

Serpentine Pavilion 2017, designed by Francis Kéré. Serpentine Gallery, London (23 June – 8 October 2017) © Kéré Architecture, Photography © 2017 Iwan Baan  Francis Kéré, © Erik Jan Ouwerkerk

Francis Kéré, © Erik Jan Ouwerkerk

Architecture50Cover#bd0000Aligner à gauche

Architecture50Cover#bd0000Aligner à gauche © Louvre Abu Dhabi, Photography by Mohamed Somji

© Louvre Abu Dhabi, Photography by Mohamed Somji  Louvre Abu Dhabi © Abu Dhabi Tourism & Culture Authority, Photography Sarah Al Agroobi, Architect Ateliers Jean Nouvel

Louvre Abu Dhabi © Abu Dhabi Tourism & Culture Authority, Photography Sarah Al Agroobi, Architect Ateliers Jean Nouvel

FashionArchitecture50Cover#fbfafaAligner à gauchePhotos by Khalil Nemmaoui

FashionArchitecture50Cover#fbfafaAligner à gauchePhotos by Khalil Nemmaoui Yves Saint Laurent museum, Marrakech

Yves Saint Laurent museum, Marrakech  Yves Saint Laurent museum, Marrakech

Yves Saint Laurent museum, Marrakech  Yves Saint Laurent museum, Marrakech

Yves Saint Laurent museum, Marrakech

50Cover#7d0808Aligner à gauche

50Cover#7d0808Aligner à gauche Rockbund Project, Shanghai, China © Christian Richters

Rockbund Project, Shanghai, China © Christian Richters  Rockbund Project, Shanghai, China © Christian Richters

Rockbund Project, Shanghai, China © Christian Richters  Rockbund Project, Shanghai, China © Christian Richters

Rockbund Project, Shanghai, China © Christian Richters  Rockbund Project, Shanghai, China © Christian Richters

Rockbund Project, Shanghai, China © Christian Richters  Rockbund Art Museum Shanghai, China © Simon Menges

Rockbund Art Museum Shanghai, China © Simon Menges